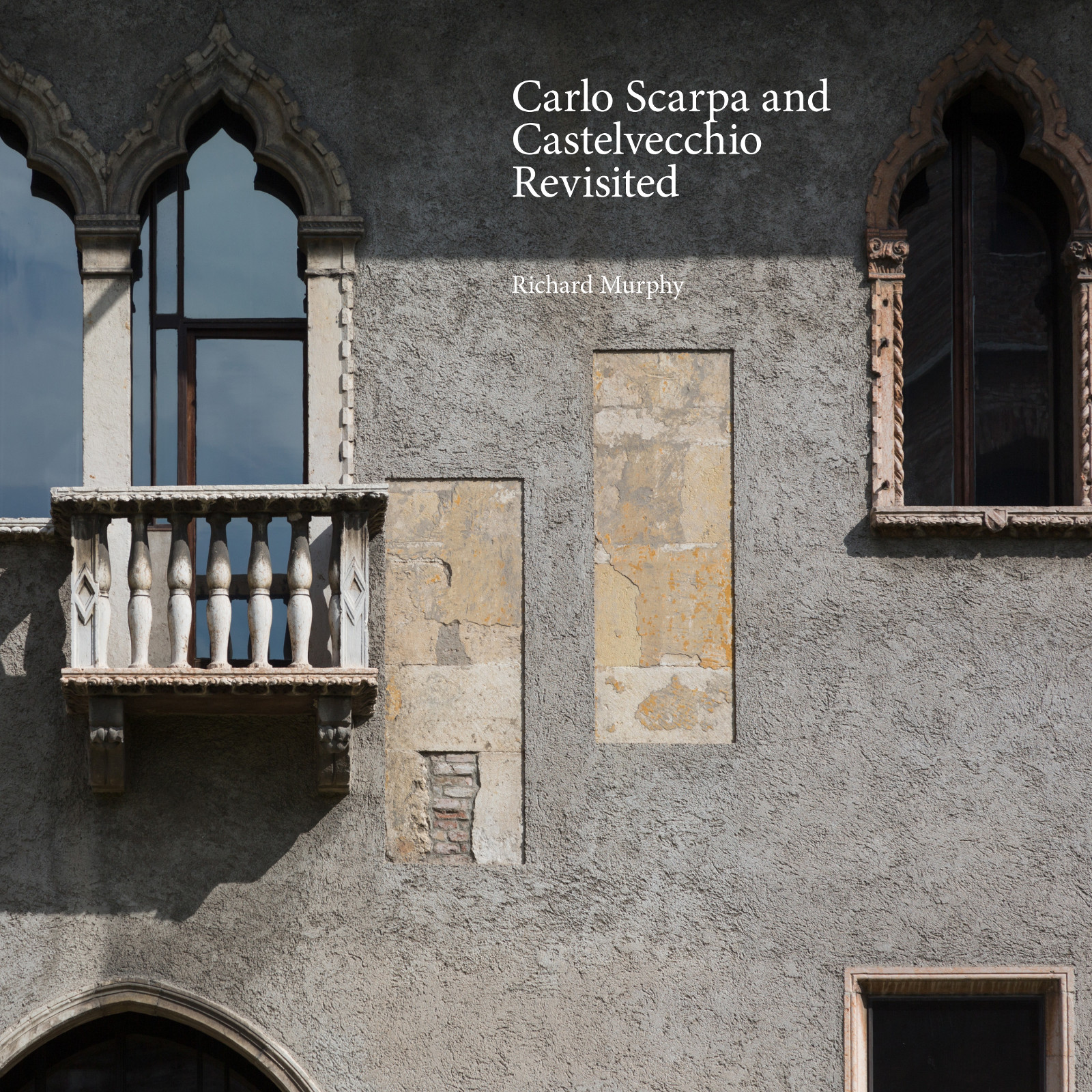

Carlo Scarpa and Castelvecchio Revisited

English Language Edition

Richard Murphy, 2016

Introduction To Carlo Scarpa and Castelvecchio Revisited

Carlo Scarpa worked on the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona intermittently between 1957 and 1975. It is perhaps his most important project. His work there draws on all his remarkable skills. It demonstrates how to work creatively within a building which already possesses a complex history. It is a magnificent example of his highly personal language of architecture, not least his incredible eye for detail and mastery of the crafting of materials. And it contains a museum exhibition which is as radical and timeless today as the day it opened in 1964 and has served as an inspiration to museum designers ever since. His most extraordinary achievement is where all these themes coincide in the astonishing display of the equestrian statue of Cangrande, perhaps the most remarkable setting for a single work of art ever made.

This book analyses not just Scarpa’s work as we find it today, and in great detail, but also introduces the reader to the complex history of the building as well as sequences of Scarpa’s own highly revealing drawings; witnesses to a brilliant curiosity and holistic approach to design where the art and architecture are completely complimentary.

Richard Murphy surveyed the whole building in 1986, and later interviewed many of Scarpa’s collaborators, including his craftsmen, and analysed all Scarpa’s drawings leading to three exhibitions and a book published in 1990. However, Carlo Scarpa and Castelvecchio Revisited is in many ways unrecognizable from its predecessor. It is neither a second edition nor is it a completely new analysis. It has started with the 1990 publication but the format is larger and 198 pages have grown to 384. Almost twice as many Scarpa drawings have been selected (some were unknown in 1990), and this time they are printed in colour with a reference system to guide the reader to details within them. Large sections of the accompanying text have been rewritten and expanded and there are two new chapters. Perhaps most importantly there are many more photographs, both of the building at various phases of its complex life but also superb contemporary colour photography by Peter Guthrie assisted by Matthew Hyndman.

The Contents

After a preface by Margherita Bolla the Director of the Museum since 2015 and a foreword by the architectural writer and critic Professor Kenneth Frampton, the initial chapters consist of an overview of Scarpa’s work in the castle, an explanation of the history of the building since it origins in the 12th century, a description of Scarpa’s method of working, an overview of his drawings and a discussion of his approach to museum and exhibition design.

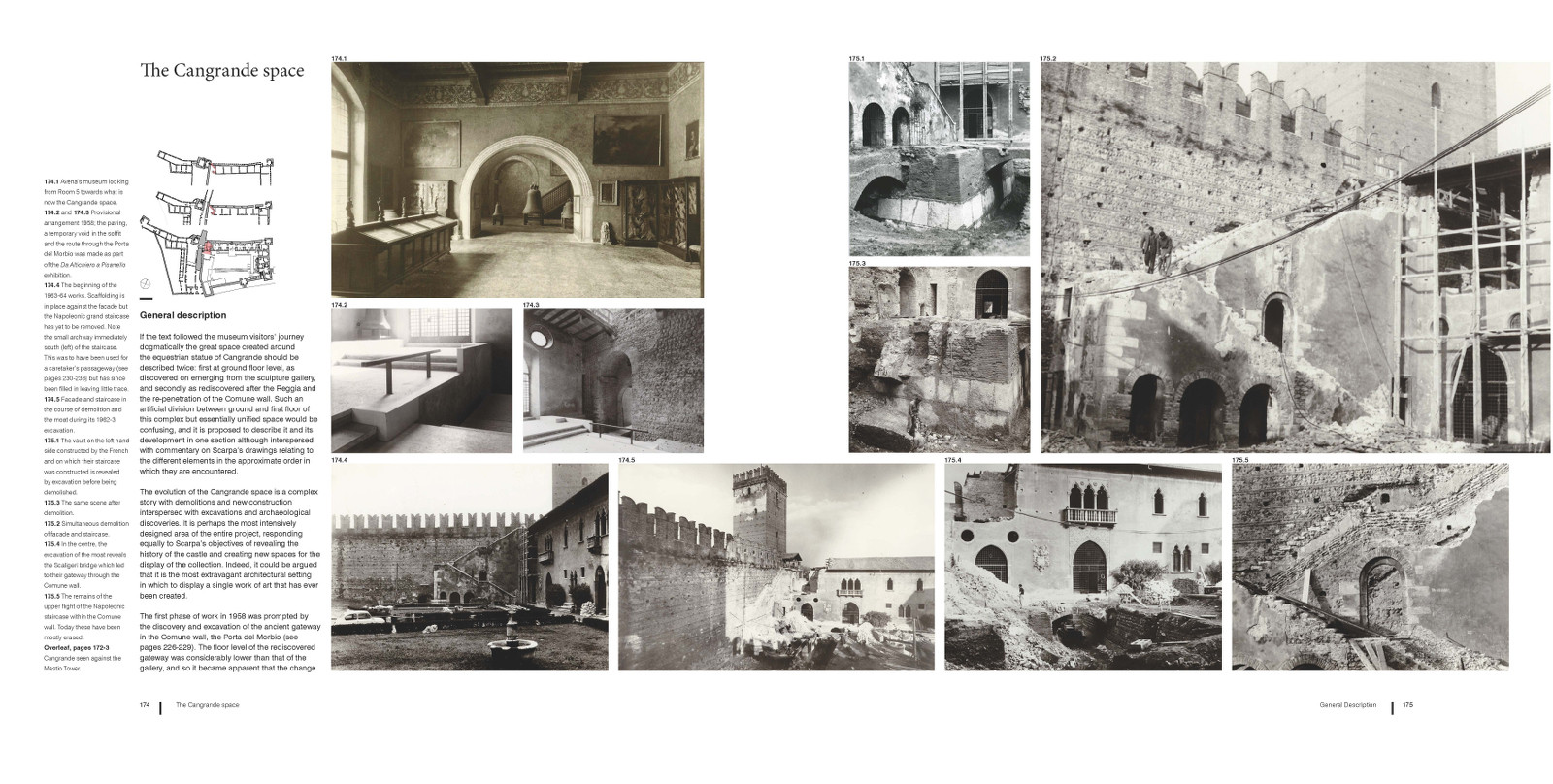

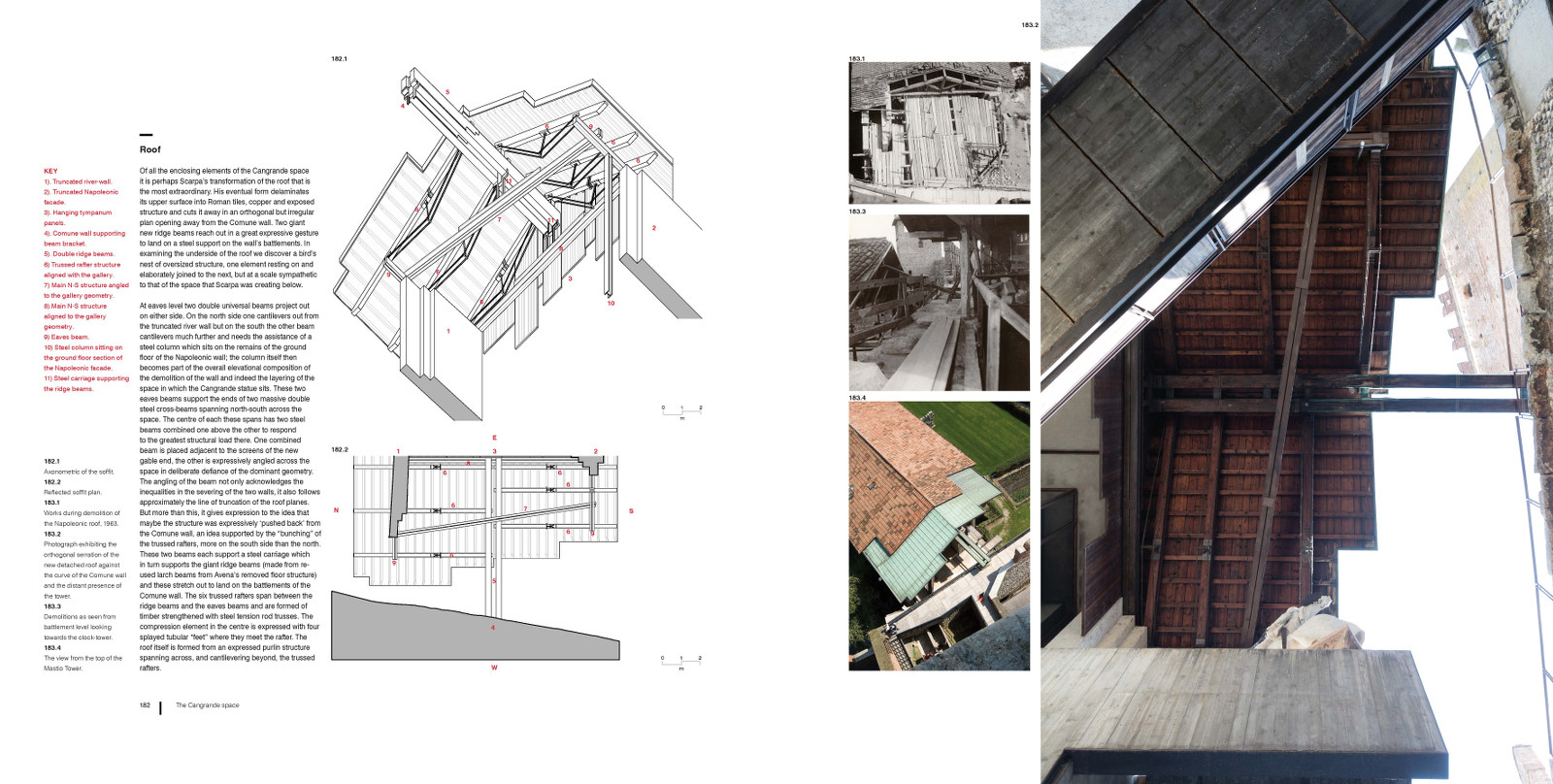

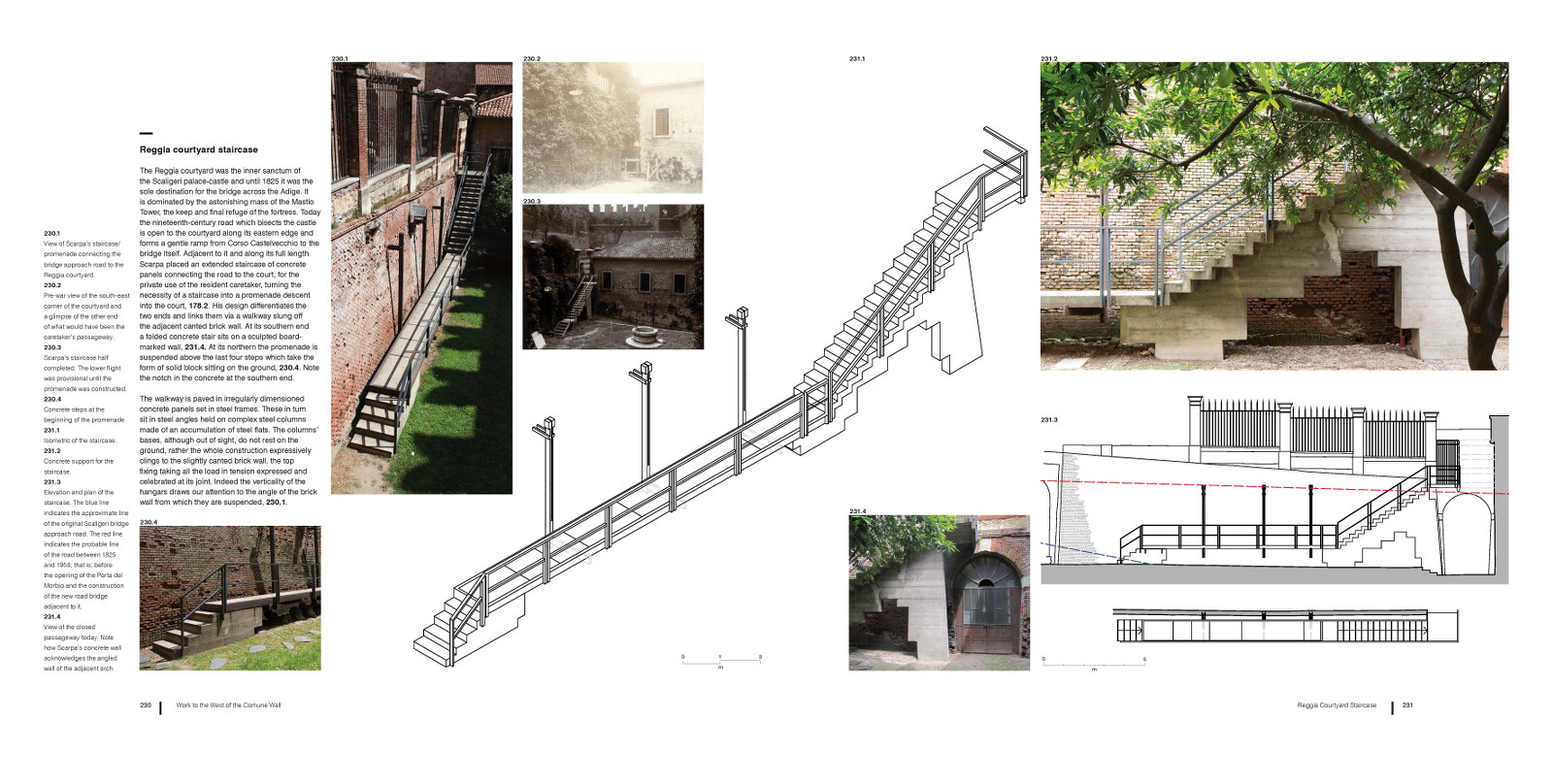

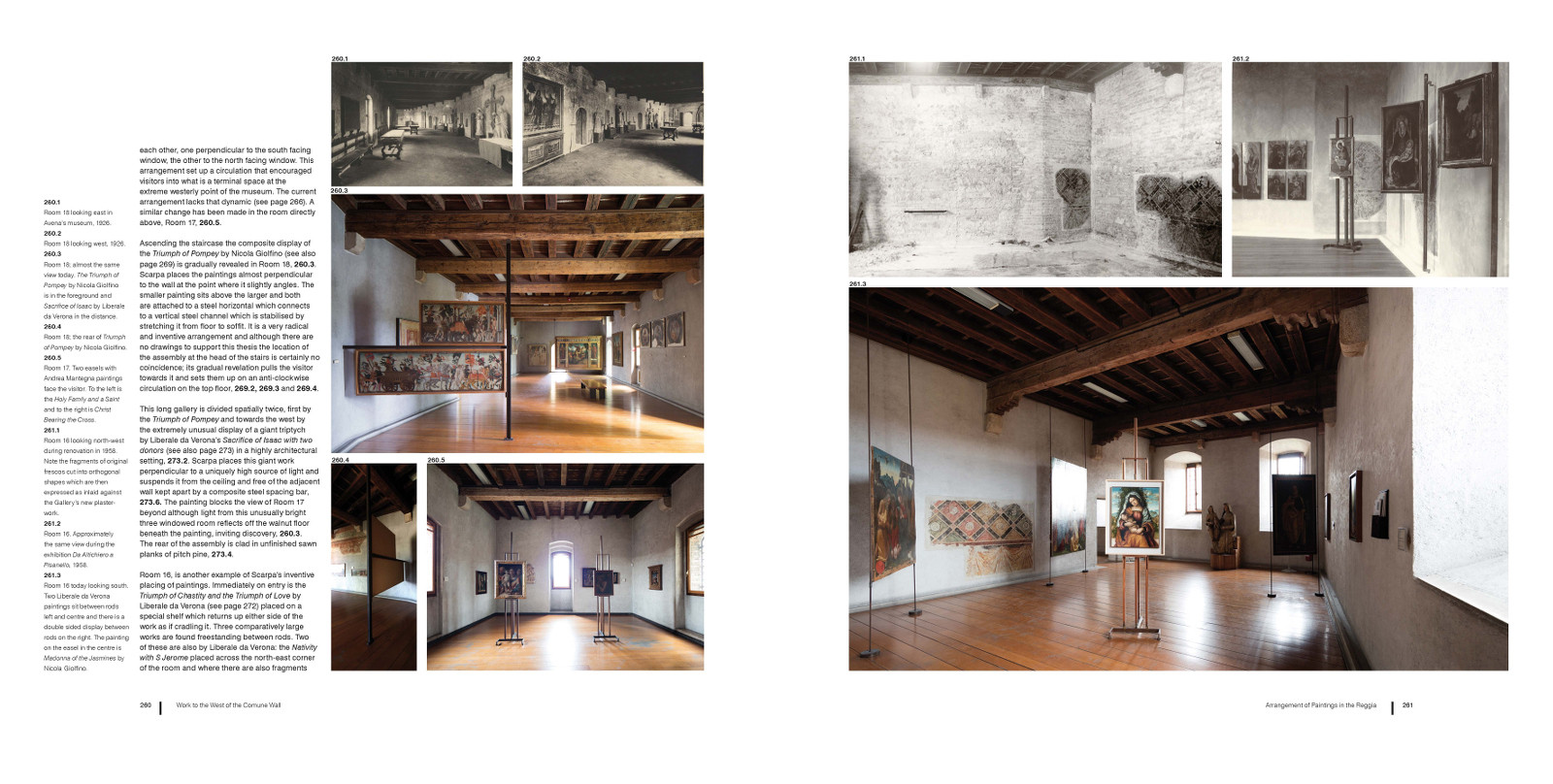

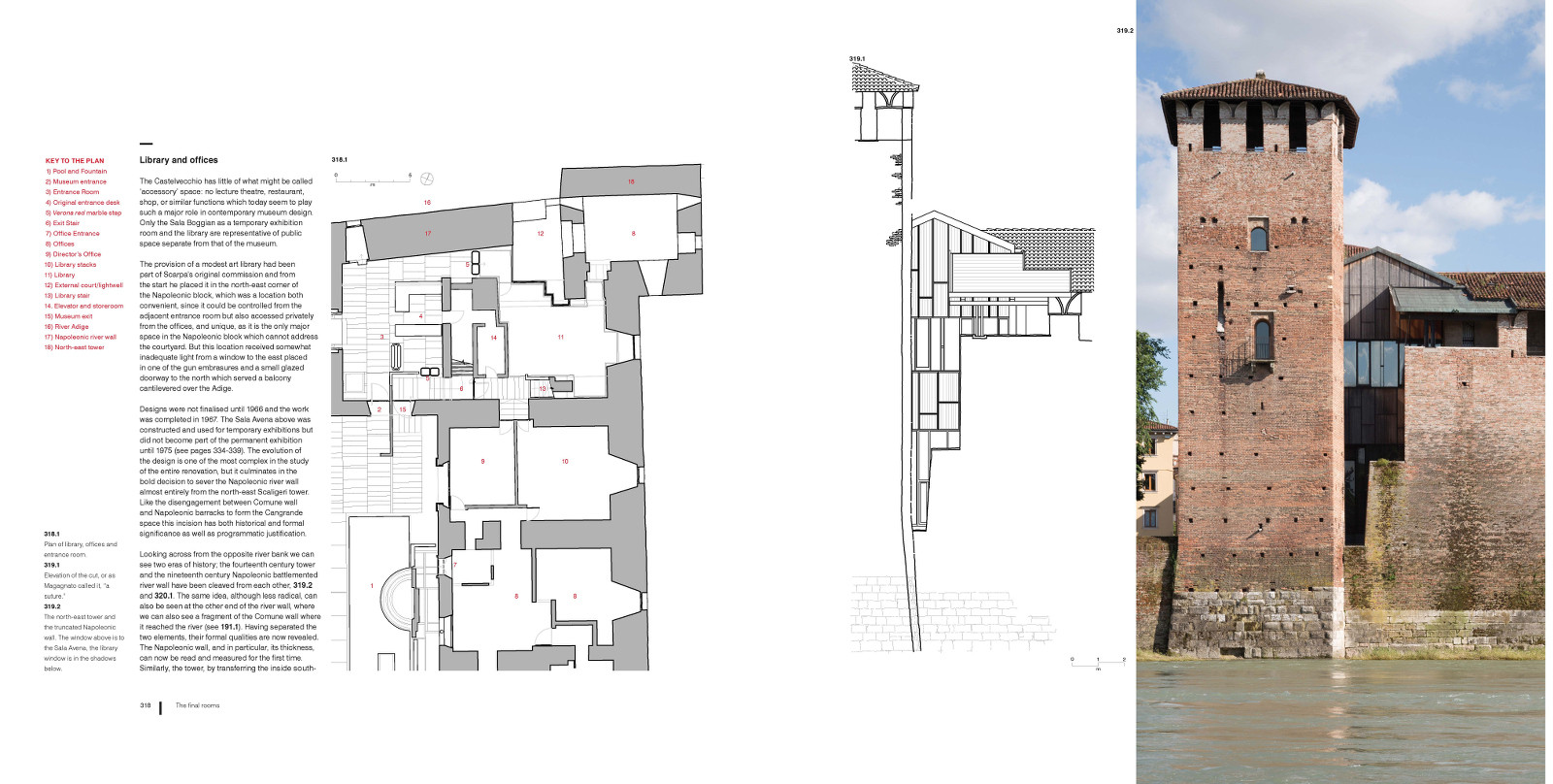

The majority of the book is divided into five areas in the order in which a visitor encounters them: "The Great Courtyard”, “Entrance room and sculpture gallery”, “The Cangrande space”, “Work to the west of the Commune wall" and "The final rooms".

The concluding chapters feature articles by Scarpa’s client the late Licisco Magagnato (1921-1987) and by his assistant the late Arrigo Rudi (1929-2007). There are also two chapters by Alba Di Lieto. She is an architect who has worked in the Museum since 1979 and she has written about the changes since Scarpa’s death in 1978 and also has written a detailed specification of materials used in the building. Finally Ketty Bertaloso who also works in the Museum has written about the digital archiving of Scarpa’s drawings.

The Importance of Castelvecchio

Carlo Scarpa was born in Venice on 2 June 1906. His family moved to Vicenza in 1908 but in 1919 his mother died and his father moved the family back to Venice. Scarpa enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts between 1922 and 1926 where he took his Diploma. He became apprenticed to Francesco Rinaldo, marrying Rinaldo’s niece, Onarina Lazzari in 1934. His son, Tobia, was born in 1935. He taught interior design and drawing at the University in Venice for most of his life but never took the professional examinations to become an architect. Scarpa moved to Asolo in 1962 and in 1972 moved again, this time back to Vicenza. In 1978 during a visit to Japan he tripped down a staircase in Sendai and died a few days later. His body was brought back to Italy and buried, according to his wishes, between the village gravestones and his own creation of the Brion family Cemetery outside the village of S. Vito di Altivole, just south of Asolo.

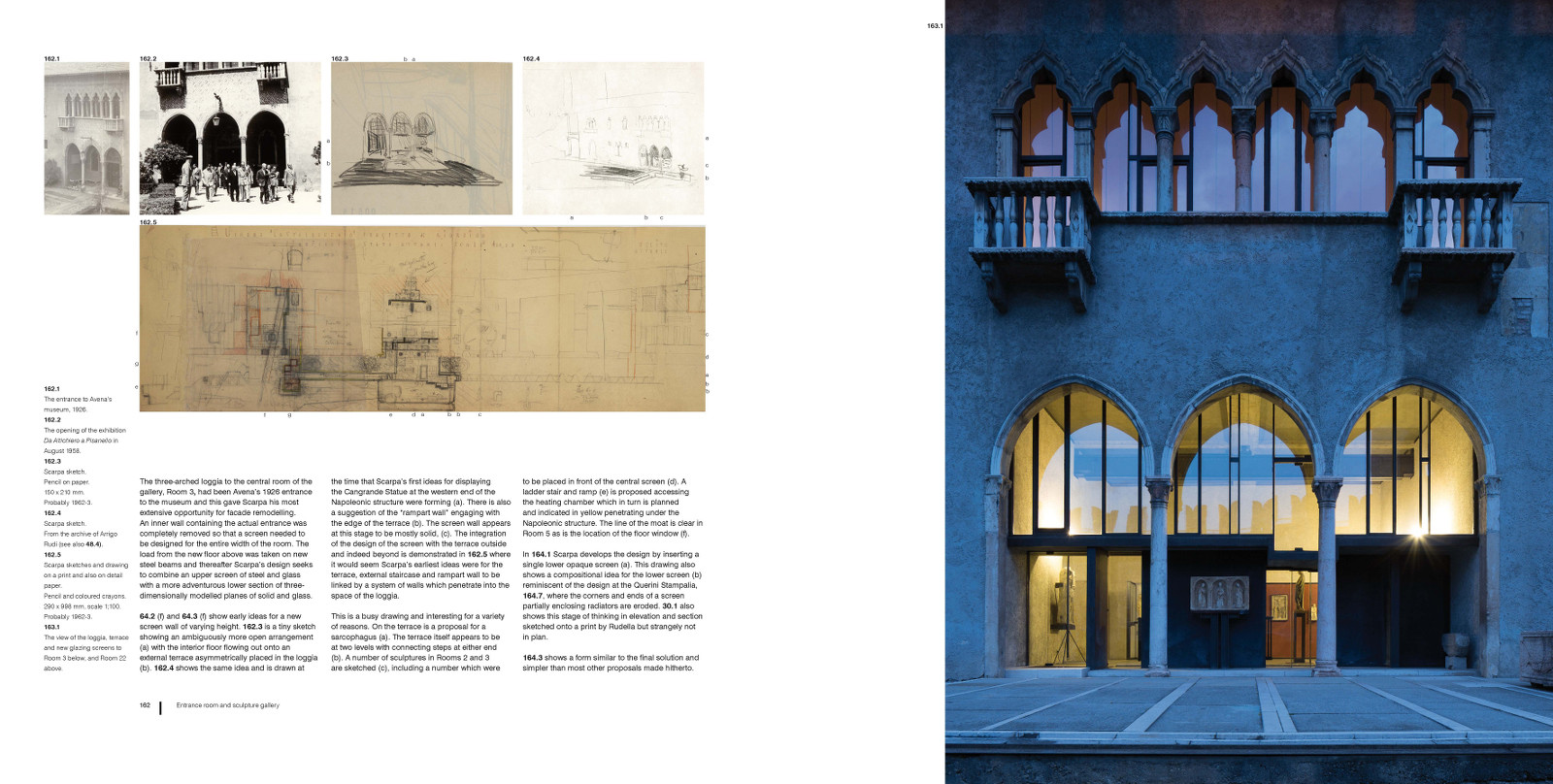

Scarpa worked on the remodelling of the Castelvecchio Museum, Verona in two main phases between 1957 and 1964 with additional phases completed in 1967 and 1975. The project sits centrally in his career amongst his major works. It is preceded by the Olivetti Showroom, Venice and the museum projects at Palermo, Possagno and Correr Museum, Venice; and is followed by the Ottolenghi House, the posthumously completed headquarters of the Banca Popolare di Verona and the most profound project of his opus, the aforementioned Brion cemetery at S. Vito di Altivole. A number of other important commissions were designed during the same period as his work in the museum - most notably the alterations to the Querini Stampalia, Venice and the Venetian pavilion ‘The Sense of Colour and the Control of the Waters’ in the 1961 Turin Exhibition, both projects of particular relevance for his thinking at the Castelvecchio and mutually influential.

When Scarpa died in 1978 very little of his work had been published. The Architectural Review in December 1973 reviewed an exhibition at the Heinz Gallery in London, the Italian architectural magazines Controspazio and Rassegna had both published special editions on Scarpa’s work in 1981 but Magagnato’s catalogue to the exhibition of a selection of the Castelvecchio drawings in 1982 represented the first monograph. This was the first of what has since become a proliferation of publications, seemingly without end.

Why the astonishing interest in Scarpa’s work; and why was there such a delay in its widespread appreciation? Within his own lifetime and for some time afterwards Scarpa’s work was still judged as anachronistic, small-scale and craft-intensive. Perhaps it is because, as Bruno Zevi has rightly pointed out, he left us no memorably inventive plans. More likely, however, is the relative inaccessibility of his work through the medium of photographs and the written word. All great buildings once visited usually exceed the expectations of the informed visitor, but rarely to the degree experienced with those of Scarpa. In his case photographs are a wholly inadequate preparation. Only directly can the rich sensory experience of his architecture be revealed: the unfolding of spaces and vista, the sounds of water, the movement of light on texture, the delight in the discovery of details, the touch of materials. To comprehend fully his genius one needs to move through his spaces with all senses alert and working together. In Murray Grigor’s 1996 Channel 4 documentary Arrigo Rudi memorably commented that, ‘it is impossible to visit a building by Scarpa with your hands in your pockets. You must touch..’

Aside from the Castelvecchio’s central position in Scarpa’s career, to choose to study this one building from his opus is felicitous for a number of reasons. Firstly of course it is a museum, and permanent and temporary exhibition design is the field of work that Scarpa made his own and in which, probably, his influence is at its greatest. Castelvecchio is certainly the largest example and contains a whole variety of spaces for displaying art, not least of course, the extraordinary setting of the equestrian statue of Cangrande.

Secondly, the Castelvecchio is an intervention in an historic structure, and is the most complex and didactic of them all particularly considering the way in which Scarpa set about to display the many different layers of history pre-existing his own intervention. Until Scarpa, architectural energy expended on working within existing buildings was not considered mainstream. Indeed one struggles to cite a single building or project from any of the “greats” of modern architecture of this type of work. Since Scarpa, and Castelvecchio in particular, it is considered just as valid as new constructions.

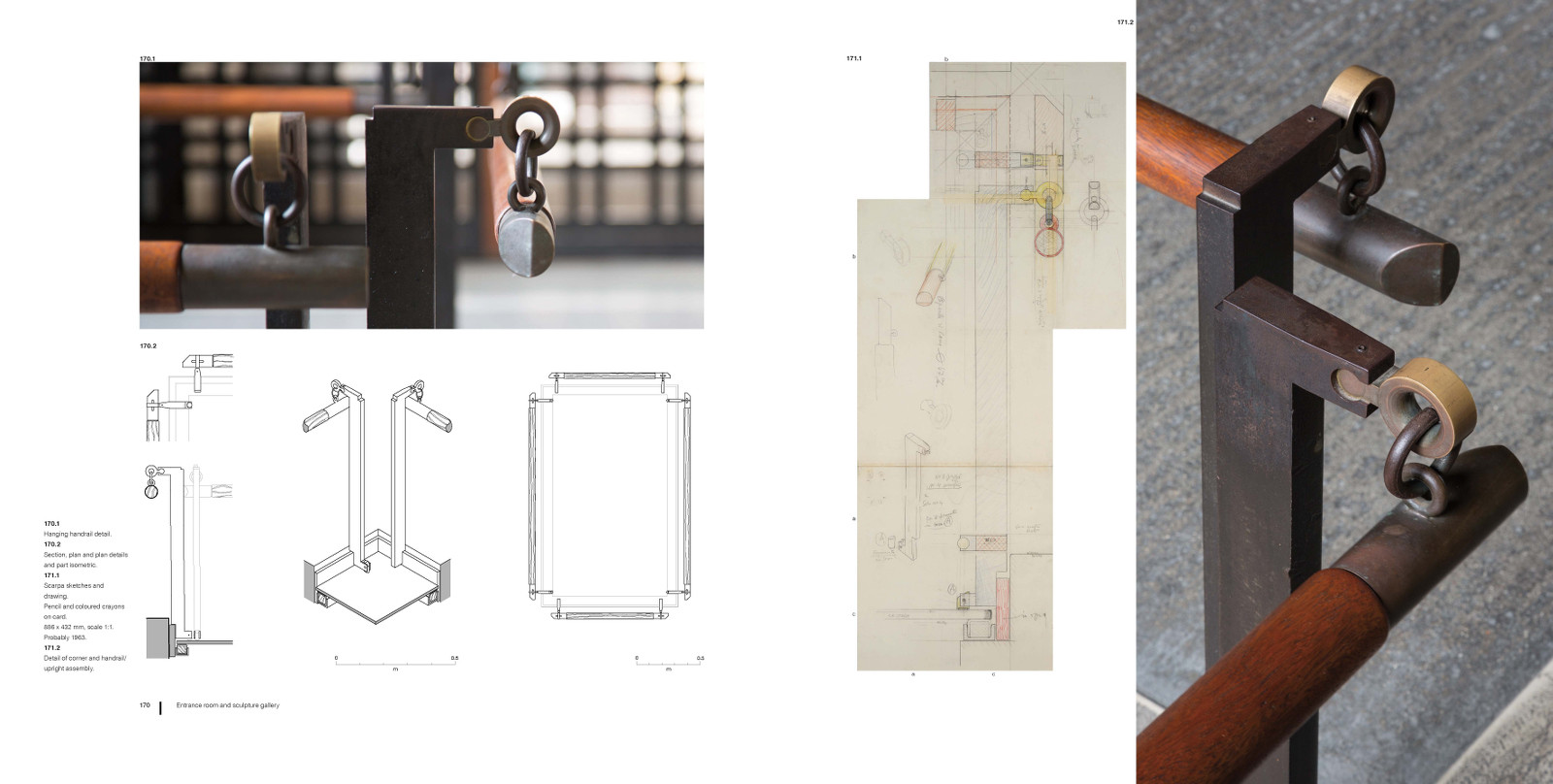

Thirdly, whilst to an extent constrained by the historic fabric of the existing building, the full vocabulary of Scarpa’s remarkably personal and twentieth-century architectural rhetoric can be examined. It also contains the largest collection of examples of his celebrated detailing. Staircases, doors, windows, handles, junctions - all can be studied in abundance and have been documented in the measured drawings. The richness of the detailing and the density of design answer to a degree the criticism of the lack of both in much of twentieth century modernism.

Fourthly, Scarpa’s architecture, Rudi once commented, is timeless. It cannot be dated to the 50’s or 60’s and he attributed that to the fact that Scarpa rarely looked at architectural magazines so was unaffected by the fashionable, preferring instead the world of artists, a world brought to Venice every two years at the Biennale. It is however not without roots and in particular the reinterpretation of Venice is a phenomenon we can trace in all his buildings.

Finally, Castelvecchio is unusual in that the Museum owns and has catalogued almost all the surviving drawings for the project. So the designing and making of the building can also be studied; a series of private design journeys made available to all through the examination of the development of ideas through sequences of drawings. The drawings also bear witness to the remarkable series of relationships between Scarpa and Magagnato, the Commune, his assistants Arrigo Rudi and Angelo Rudella and, not least, the craftsmen and artisans who realised his ideas.

And so it is hoped that this study will be useful for those concerned with museum design, those concerned with interventions in historic buildings, those who would like a source book of detailing and construction and for those generally interested in the work of Scarpa, both in the built project as recorded here in photographs and measured drawings, and in the process as witnessed through the sequences of Scarpa’s drawings selected. And for the visitor to the Museum itself, it is hoped that the study will act as both a useful guide and worthy souvenir.

What the Critics Say

"Outside of northern Italy no-one has contributed more to our understanding of Carlo Scarpa than the Edinburgh based architect Richard Murphy....as this brilliant and exhaustive study of the Castelvecchio reveals."

- Kenneth Frampton, WARE PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE AT THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE PLANNING AND PRESERVATION, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK

"Regarding Richard Murphy’s first, 1990 edition of his book on Scarpa’s Castelvecchio, I wrote in 2013: ‘This exemplary study, including the measured drawings, remains one of the best books on Scarpa,’ a statement that also implied my belief that the book would never be surpassed. Murphy has proved me wrong on this last count by publishing the new enlarged, expanded and exhaustively illustrated edition of what was already considered a canonical study of Carlo Scarpa and his greatest work, the Castelvecchio. I have long considered the single-building monograph to be the most compelling and effective way to present the qualities and character of the building, as well as the design process and ordering principles of its architect. Murphy has now given us—yet again—not only the canonical study of the Castelvecchio and its architect, but what will undoubtedly be recognized as one of the most comprehensive and insightful single-building monographs ever published. I am confident in saying this second edition will never be surpassed, for there is nothing left unsaid or unexplored regarding the building or its architect. This book is a true masterpiece, as befits the Castelvecchio, Scarpa’s architectural masterpiece that the book so perceptively and propitiously brings into presence for us, the readers."

- Robert McCarter, RUTH AND NORMAN MOORE PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE, WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS.

"This is a welcome re-appearance of this classic work that should never have been out of print. Richard Murphy’s study, now even more comprehensive than before, is fundamental to the burgeoning activity of interventional design. This new edition is a strikingly handsome production, with new photography and Scarpa’s drawings looking fresher than ever. The author’s comprehensive analysis, both in visuals and in text is one of the wonders of architectural criticism. Murphy, along with Giancarlo di Carlo working in Urbino, can rightly be considered as the pioneer, the initiators of a structured approach to the task of altering existing works of architecture. The publication of this new edition will help to counter the dumb excesses of some recent work across Europe and beyond. It will also one hopes help to begin a conversation that is still lacking in this country between designers, architects and historians with regard to the proprieties and otherwise, approaches to be encouraged and those that should be forbidden. Murphy, more than anyone, has been responsible for the universal recognition of Scarpa’s genius in his work in Verona. Any description of the museum and Scarpa’s involvement with it will tend to end up as a précis of part or all of Murphy’s books."

Fred Scott, AUTHOR OF ON ALTERING ARCHITECTURE, ROUTLEDGE 2008, LONDON’

"Such an intense and sustained investigation of one building and one architect by another is rare: Murphy’s dedication to Scarpa and the Castelvecchio is absorbingly interesting. This is a search for the absolute essence of architecture, conducted with exemplary scholarship and lifelong enthusiasm."

Hugh Pearman, EDITOR, RIBA JOURNAL’

Buy Now: £75.00

English Language Edition

384 pages. Retailing at £75.00. Postage to anywhere in the world included in the price.

Please contact sales@breakfastmissionpublishing.com if you have any queries.

The English language edition is now out of print. Some bookshops may still have copies.